From hospice to palliative and supportive care or the other way around

More than 60 years have passed since Dame Cicely Saunders composed a 10-page proposal for a hospice, and therefore, established a foundation for the hospice movement. Her dream project provided hospice care for 100 terminal cancer patients in London.7 Many of the principles of the hospice movement were retained and adopted by a Canadian physician, Balfour Mound, who first used the term palliative care in a treatment setting aimed at symptom relief in 1974.8 Almost 20 years later, the importance of palliative care was recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO). Consequently, the expert committee on cancer pain and palliative care was established, which then called for the integration of efforts directed at maintaining patients’ quality of life (QoL) at all stages of cancer treatment.9 The initial report of the committee was later followed by an updated definition of palliative care, in which pain relief and QoL were even more emphasized (Text Box 1).

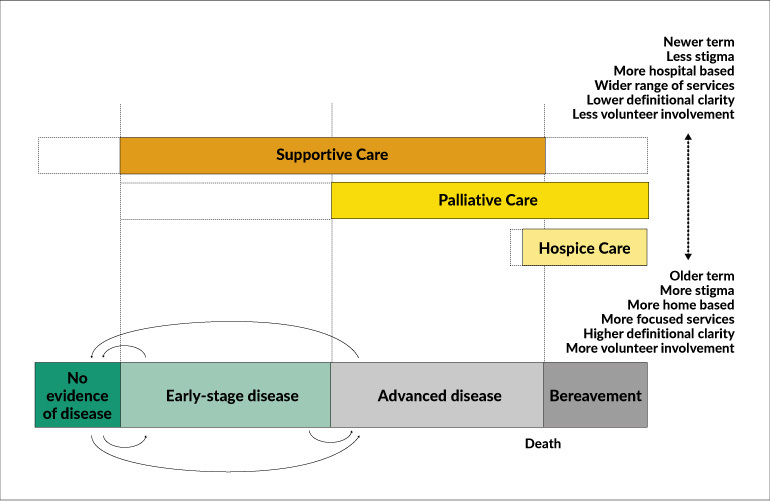

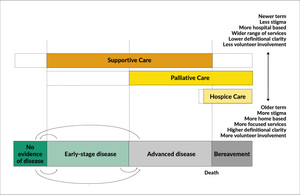

Over the past few decades, many different terms to describe palliative care have evolved, among which supportive care, first used by Page in 1994, has gained immense popularity.11,12 Today, the most commonly used definition was proposed by The Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer: “Supportive care in cancer is the prevention and management of the adverse effects of cancer and its treatment. This includes management of physical and psychological symptoms and side-effects across the continuum of the cancer experience from diagnosis through anti-cancer treatment to post-treatment care. Enhancing rehabilitation, secondary cancer prevention, survivorship and end-of-life care are integral to supportive care.”13 However, all these terms are often used interchangeably and some would claim they are euphemisms, while others express the need for standardized definitions. Among other factors, the lack of definitions for key terms may also contribute to difficulties in integrating palliative care into standard oncology care.14

Why should early palliative care be integrated into standard oncology care?

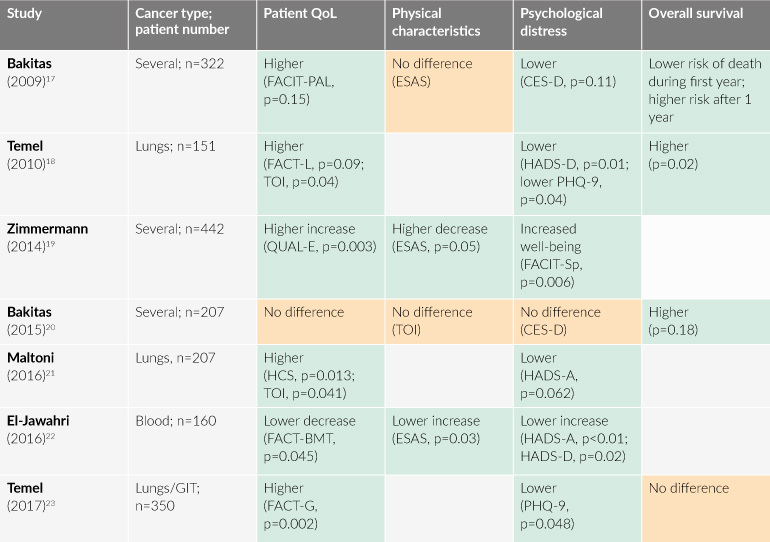

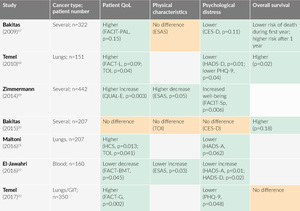

The Swiss National Guidelines suggest concurrent palliative care and standard oncological care at the time of initial diagnosis.15 This is supported by the results of several studies included in a systematic review and meta-analysis, where it was shown that QoL in patients receiving early palliative care was significantly higher.16 Apart from QoL, early palliative care also leads to several other improvements in the patients’ physical characteristics as well as psychological condition (Table 1).

Already in 2010, Temel et al. have reported that early palliative care not only improves QoL, but also draws attention to resuscitation preferences and less aggressive end-of-life care of patients with lung cancer.17 Furthermore, prolonged survival was observed in advanced cancer patients who received specialist palliative care while undergoing initial anti-cancer therapy. Median survival in the group assigned to early palliative care (n=77) was 11.6 months versus 8.9 months in the standard care group (n=74).17 Recently, the increased QoL with early palliative care versus usual care in patients with lung cancer (p<0.05 through 24 weeks), has been confirmed by the same research group once more (Figure 1).18

While a survival benefit due to the early involvement of palliative care is still to be demonstrated for different types of cancer, there is sufficient evidence supporting that it leads to better patient and caregiver outcomes.11,17–23 Therefore, whether palliative care should be integrated into the standard care for cancer patients is no longer a subject of discussion, but rather, how it should be integrated into various healthcare systems and how it should be adapted to the specific needs of different patient populations are the key questions to be addressed.24,25

When is the optimal time?

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) specifically recommends that patients with advanced cancer should receive dedicated palliative care services concurrent with active treatment, no later than 8 weeks after the initial diagnosis of the disease.26 This is supported by Bakitas et al. (2015), who showed that a delay of 3 months in the introduction of early palliative care is associated with a significant difference in the survival rates after 1 year (63% for the early group versus 48% for the delayed group, p=0.038).20

However, different palliative policies around the globe, including the latest guidelines from the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), have been largely influenced by the WHO definition, which recommends that palliative care is “applicable early in the course of illness,” and therefore, suggests palliative care for cancer patients in a framework not limited to advanced cancers.2,10 Thus, the best model to describe palliative care in this broad sense, taking into consideration the varying needs of the patients, would be the adapted time-based model proposed by Hui and Bruera (Figure 2).25 This model covers supportive care, palliative care, and hospice care, according to the stage of cancer. Supportive care is the basis for this model, including patients receiving curative therapy, and should be offered at the time of diagnosis. Palliative care represents more specialized symptomatic relief for patients with advanced cancers, while hospice care comes with end of life care, mostly when the expected survival is no longer than 6 months.11,25

Who should be referred?

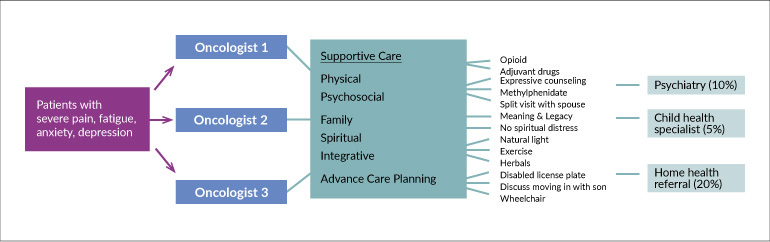

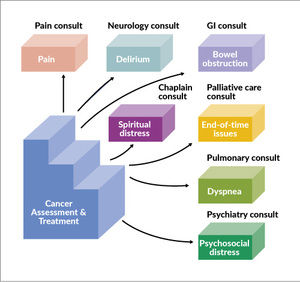

The conceptual patient-centric system-based model (Figure 3), developed by Hui and Bruera, depicts how a typical patient should navigate the healthcare system to access initial supportive care.25 The current situation usually does not seem to be efficient for every patient, therefore, the integrated model is recommended, in which the patients in need would have better access to palliative care regardless of which oncologist they visit. This could be best achieved with commonly known and detailed predefined criteria, therefore, different recommendations have been proposed, with different features taken into consideration.27–30 Consequently, a consensus was reached on 11 major criteria and 36 minor criteria for specialist palliative-care referral.31

A significant burden is also associated with informal caregiving, leading to negative health outcomes and decreased general well-being.32 Therefore, ASCO recently recommended that caregivers of patients with early stages of cancer may also be referred to palliative care services.26 Some authors report that effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in caregivers of patients remains unclear, while others recommend psychoeducation, supportive care interventions, and cognitive behavioral interventions in order to decrease caregiver-related strain and burden.32,33 It remains rather unclear, how all of this can be implemented in practice.32

How much should be done by oncologists?

According to the initial ESMO guidelines from 2003, “medical oncologists must be skilled in the supportive and palliative care of patients with advanced cancer … They should be skilled in communication, and they should be familiar with the evaluation and management of psychological and existential symptoms of cancer, the interdisciplinary care of patients with advanced cancer, palliative care research, ethical issues in the management of patients with cancer, and preventing burnout …”34

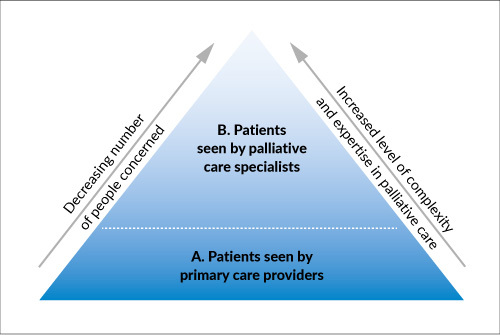

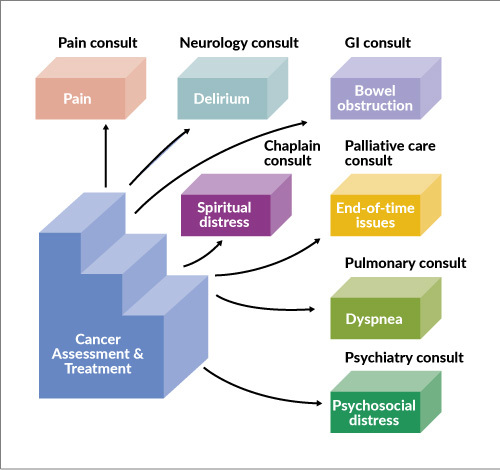

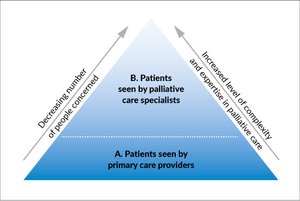

At this point, it is important to mention two other conceptual models of palliative care to give a sense of how much palliative care is expected from oncologists, i.e. the palli-centric provider-based model (Figure 4) and the onco-centric issue-based model (Figure 5).25,35 The provider-based model primarily concentrates on how much palliative care should be provided by a clinician based on the level of complexity of a patient.25,36 Primary palliative care (A) is provided by doctors, who treat the patients on a regular basis, and therefore, need to provide a high basal level of supportive care. This mainly refers to oncologists and primary care providers. Patients with more advanced disease and more complex care needs should be referred for secondary and tertiary palliative care (B), in which specialist palliative clinicians would either see them as consultants or as the attending physicians in acute palliative care units.

To help oncologists manage their daily issues and deliver the best possible primary palliative care, the more accurate issue-based model was developed.25,35 The most recent upgrade of this integrated model enables prompt and extensive standardized palliative care with concurrent oncological care, normalizes the initiation of supportive and palliative care, and finally minimizes the demand for oncologists to provide both high-quality oncological and supportive care. All in all, according to the authors, this model “enables oncologists to provide as much or as little supportive care as they desire, knowing that their patients will always be able to receive high-quality palliative care.”25

Neither last nor least

To summarize, there are multiple innovative approaches to promote the integration of early palliative care into standard oncology care. Given the heterogeneity of cancer center infrastructure, patient populations, resource availability and clinician trainings, there is no universal model that can be used. The vision of integration should be defined in advance so that the current challenges can be addressed effectively. But most importantly, the center of care should always be the well-being of patients rather than statistically significant data points.

“Being mortal is about the struggle to cope with the constraints of our biology, with the limits set by genes and cells and flesh and bone. Medical science has given us remarkable power to push against these limits, and the potential value of this power was a central reason I became a doctor. But again and again, I have seen the damage we in medicine do when we fail to acknowledge that such power is finite and always will be. We’ve been wrong about what our job is in medicine. We think our job is to ensure health and survival. But really it is larger than that. It is to enable well-being. And well-being is about the reasons one wishes to be alive. Those reasons matter not just at the end of life, or when debility comes, but all along the way. Whenever serious sickness or injury strikes and your body or mind breaks down, the vital questions are the same: What is your understanding of the situation and its potential outcomes? What are your fears and what are your hopes? What are the trade-offs you are willing to make and not willing to make? And what is the course of action that best serves this understanding?” Atul Gawande37

.__.jpg)

.__.jpg)