Introduction

Vasomotor symptoms (VMS), primarily hot flashes and night sweats, are among the most frequent and burdensome side effects in women with breast cancer, particularly those receiving endocrine therapy.1–4 Compared with symptoms associated with natural menopause, treatment-induced VMS may be more abrupt, severe and are strongly associated with non-adherence or discontinuation of therapy.3,5–7 Effective management is therefore essential, not only to alleviate symptoms and improve quality of life (QoL) but also to support adherence to life-prolonging endocrine treatments.

Because hormone replacement therapy is contraindicated in patients with estrogen receptor-positive disease due to concerns about cancer recurrence, safe and effective non-hormonal strategies are needed.4 Current initial approaches include non-pharmacological options, with cognitive behavioral therapy demonstrating the strongest evidence, as well as pharmacological agents that provide only modest benefit.

In recent years, novel agents targeting the neural pathways underlying VMS have been investigated in clinical trials for the treatment of moderate-to-severe postmenopausal symptoms. These include the neurokinin (NK) receptor antagonists fezolinetant, elinzanetant, pavinetant (MLE4901), osanetant (ACER-801) and SJX-653. Of these, fezolinetant and elinzanetant are now approved in Switzerland8,9 and the European Union10,11 for the treatment of moderate-to-severe VMS in postmenopausal women. Despite initially positive trial results, the development of pavinetant was discontinued in 2017 due to safety concerns.12,13 Both osanetant (ACER-801) and SJX-653 failed to demonstrate efficacy in phase II trials.14–16

This review summarizes traditional non-hormonal pharmacological options and outlines the mechanistic rationale for neurokinin receptor antagonism. It also evaluates current evidence on the efficacy and safety of neurokinin receptor antagonists in managing VMS, with a focus on breast cancer-related VMS, and explores their potential role in standard supportive care.

Traditional non-hormonal pharmacological agents

Non-hormonal pharmacological options for the management of VMS include antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) (e.g., escitalopram) and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) (e.g., venlafaxine), as well as antihypertensive medications (clonidine) and anticonvulsants (gabapentin). These medications provide only mild-to-moderate relief from hot flashes and are often limited by tolerability concerns. Reported adverse events occur in approximately 80% of patients.17,18 Table 1 summarizes key agents used for VMS management and their reported outcomes in clinical studies.19–23

Mechanistic rationale of neurokinin receptor antagonism

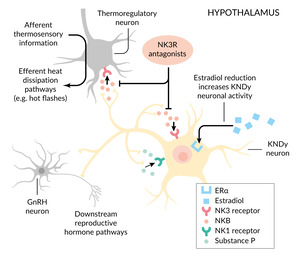

The hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis regulates female reproductive function through pulsatile secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which stimulates the anterior pituitary to release follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH).25 Elevated FSH and LH promote estrogen production by the ovaries, which establishes a negative feedback loop that suppresses further GnRH release.

Postmortem studies have identified hypertrophy of specialized neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus that co-express kisspeptin, neurokinin B and dynorphin (Dyn).26 These so-called KNDy neurons are estrogen-sensitive and play a central role in regulating the pulsatile release of GnRH; kisspeptin stimulates GnRH secretion, while neurokinin B provides stimulatory modulation and Dyn exerts inhibitory control.12,26,27 Under normal conditions, estrogen suppresses KNDy neuron activity. However, during estrogen deficiency, as occurs in natural menopause or under endocrine therapy, neurokinin B signaling is increased via the neurokinin-3 receptor (NK3R). The KNDy neurons also project to warmth-sensing areas in the medial preoptic nucleus, a key center for thermoregulation. Excessive neurokinin B signaling in this pathway contributes to thermoregulatory instability, resulting in cutaneous vasodilation and the clinical manifestation of VMS.12

KNDy neurons express both NK1 and NK3 receptors, as well as their respective ligands, substance P and neurokinin B. Estrogen deficiency induces hypertrophy and hyperactivity of these neurons, accompanied by elevated expression of both neurokinin B and substance P.26,28 This dysregulation disrupts thermoregulatory homeostasis and is considered a central mechanism in the onset of VMS.29

Figure 1 illustrates the mechanistic rationale for the use of neurokinin receptor antagonists in the treatment of VMS. These agents act by targeting the tachykinin system, particularly substance P signaling through NK1 and neurokinin B signaling through NK3 receptors, within the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center, thereby stabilizing temperature control and reducing the frequency of hot flashes.

Clinical development of neurokinin receptor antagonists

Following the identification of KNDy neurons as key mediators in the development of VMS, neurokinin receptors emerged as promising therapeutic targets. Fezolinetant, a selective NK3 receptor antagonist, demonstrated significant efficacy in reducing hot-flash frequency in two similar phase III studies involving a total of 1,022 women experiencing menopause. In the SKYLIGHT 1 study, once-daily fezolinetant 45 mg achieved a 61% reduction in hot-flash frequency by week 12, compared with a 35% reduction with placebo (p<0.001).32 In the SKYLIGHT 2 trial, the same regimen reduced hot flashes by 64% versus 45% with placebo by week 12.33 Both studies also showed reductions in symptom severity, with benefits maintained for up to one year (Table 2).32,33

The randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, dose-ranging VESTA study further demonstrated that fezolinetant compared with placebo improved quality of life (QoL) and patient-reported outcomes, including decreased interference of VMS with daily activities and better menopause-related QoL scores.36 A recent meta-analysis of five randomized clinical trials (n=2,168) reported a 22.5% greater mean reduction in VMS frequency with fezolinetant versus placebo, along with modest improvements in menopause-related QoL, particularly sleep quality.37 Moreover, a 2024 network meta-analysis of pooled data from phase III fezolinetant trials plus 23 comparator studies confirmed that fezolinetant 45 mg reduced VMS frequency with efficacy comparable to hormone therapy and superior to other non-hormonal agents.38

Elinzanetant is a dual neurokinin 1/3 receptor antagonist developed for the treatment of VMS.31 In the phase III OASIS 1 and OASIS 2 trials conducted over 26 weeks in women experiencing menopause-related VMS, elinzanetant significantly reduced the frequency and severity of moderate-to-severe VMS compared with placebo (Table 2).34 The treatment also led to greater improvements in sleep disturbances and menopause-related QoL. These benefits were sustained in the OASIS 3 trial, which confirmed efficacy over 52 weeks.39

The phase III OASIS-4 trial is the first study to specifically evaluate the efficacy and safety of elinzanetant (120 mg daily) in women with or at high risk for hormone receptor (HR)-positive breast cancer experiencing endocrine therapy-associated VMS.35 Women were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive elinzanetant for 52 weeks (n=316) or placebo for 12 weeks (n=158) followed by elinzanetant for 40 weeks. The primary endpoints were the change in mean daily frequency of moderate-to-severe VMS from baseline to weeks 4 and 12. At baseline, the mean daily frequency of moderate-to-severe VMS was 11.4 episodes in the elinzanetant arm and 11.5 episodes in the placebo arm. At week 4, elinzanetant reduced VMS frequency by –6.5 episodes versus –3.0 with placebo, corresponding to a least-squares mean difference of –3.5 (p<0.001). At week 12, reductions were –7.8 versus –4.2 episodes, yielding a difference of –3.4 (p<0.001). Elinzanetant also demonstrated significant benefits in key secondary endpoints, including improvements in sleep quality as measured by the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Sleep Disturbance Short Form (PROMIS SD SF) and in overall menopause-related quality of life as assessed by the Menopause-Specific Quality of Life (MENQOL) questionnaire.

Safety and tolerability

Overall, neurokinin receptor antagonists are considered safe in treating menopausal VMS.34–36,40,41 While some adverse events have been reported, they are often mild and manageable, with a low incidence of serious side effects.

In the large, 52-week safety study SKYLIGHT 4, treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) with fezolinetant were generally mild to moderate in severity, with low rates of fezolinetant discontinuation (fezolinetant 30 mg, 5.6%; fezolinetant 45 mg, 4.6%; placebo, 4.3%).40 The overall incidence of TEAE was similar across groups: 67.9% with fezolinetant 30 mg, 63.9% with fezolinetant 45 mg and 64.1% with placebo. Elevations in liver enzymes greater than three times the upper limit of normal (ULN) were rare and no cases fulfilled Hy’s law criteria (i.e., no severe drug-induced liver injury with alanine aminotransferase [ALT] or aspartate aminotransferase [AST] more than three times the ULN and total bilirubin more than two times the ULN, with no elevation of alkaline phosphatase and no other reason to explain the combination); therefore, they were not considered clinically relevant. With respect to endometrial safety, one patient in the fezolinetant 45-mg group developed endometrial hyperplasia, while no cases were reported in the placebo or fezolinetant 30-mg groups. Endometrial malignancy was observed in one patient in the 30-mg group, with no cases in the other treatment arms.

In a pooled analysis of the SKYLIGHT 1, 2 and 4 trials, the incidence of severe TEAEs was 3.5% with fezolinetant 45 mg compared with 2.5% with placebo.41 Serious drug-related TEAEs were reported in four patients receiving fezolinetant 45 mg (0.4%). TEAEs of special interest with fezolinetant include elevations in ALT and AST, which are mostly mild and transient.32,33 Although no cases of severe drug-induced liver injury were observed, the occurrence of liver enzyme elevations greater than three times the ULN led regulatory agencies to recommend routine liver function monitoring.8,10,41,42 The ongoing phase III HIGHLIGHT 1 trial is further assessing the safety or efficacy of fezolinetant in women with breast cancer receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy.43

Similarly, elinzanetant has demonstrated a favorable safety profile in the OASIS 1 and OASIS 2 studies, with the most frequent TEAEs being headache (7.0–9.0%) and fatigue (5.5%–7.0%) and no cases of liver injury reported.34 There were no cases of endometrial hyperplasia or malignant neoplasm in either trial.

In the OASIS-4 trial in women with severe VMS receiving endocrine therapy for breast cancer, most AEs with elinzanetant were mild or moderate, with severe events reported in 4.1% of patients.35 Serious AEs were uncommon, occurring in 2.5% of patients receiving elinzanetant versus 0.6% with placebo. During weeks 1 to 12, somnolence, fatigue and diarrhea were reported more frequently with elinzanetant than with placebo. Elevations in liver enzymes requiring monitoring were observed in five patients (including one serious case), all in the elinzanetant group; however, none met Hy’s law criteria. Between weeks 13 and 52, a small number of cancer-related events were recorded: one patient developed a new breast cancer, one experienced recurrence and one progressed to stage IV disease; in addition, one patient had suspected liver metastasis and one developed bone and liver metastases.

Managing VMS in women with breast cancer

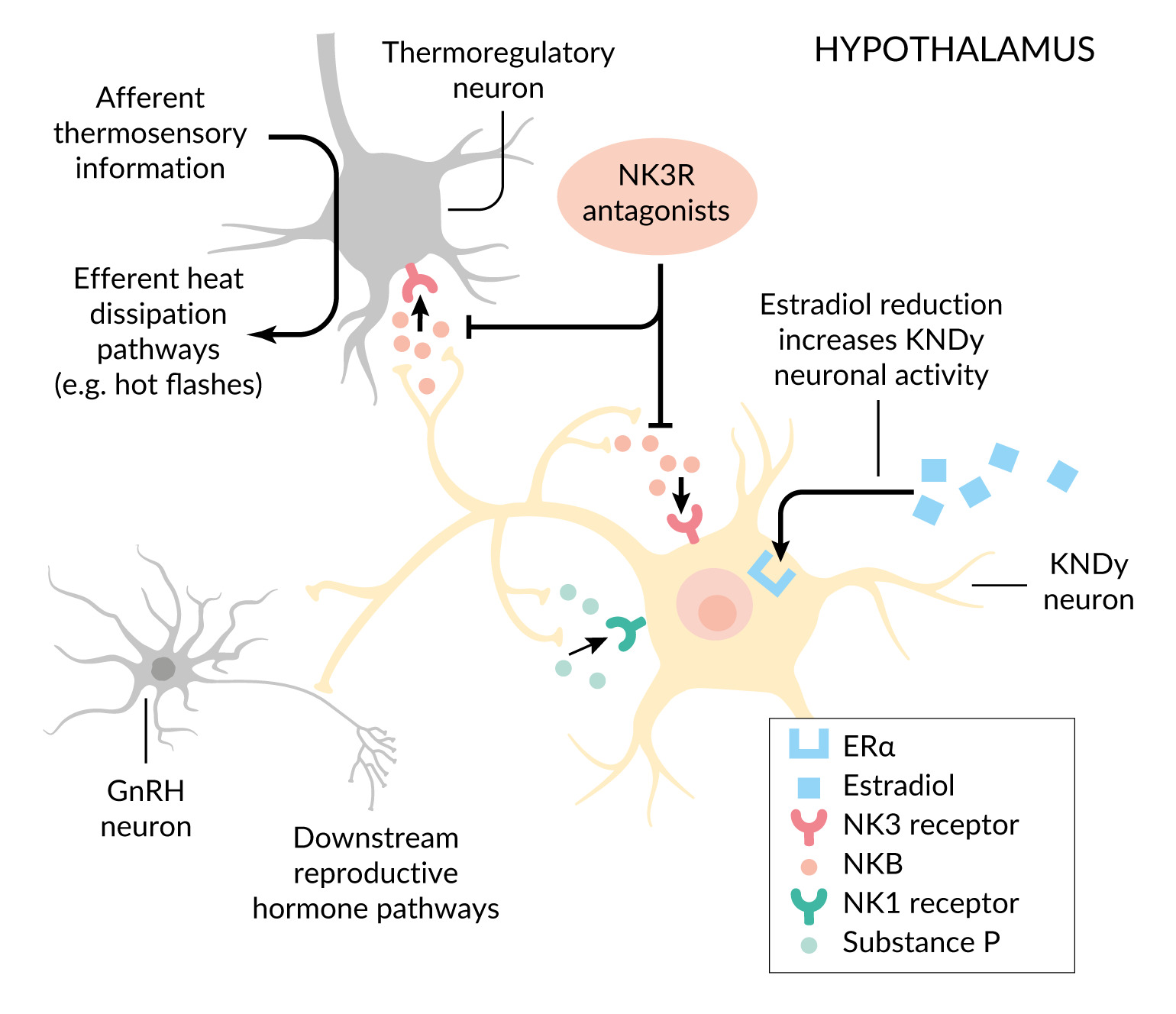

Management of VMS in women with breast cancer requires a structured approach to improve QoL and support adherence to endocrine therapy (Figure 2). The initial evaluation should include assessment of symptom burden using the Menopause Rating Scale II (MRS II),44,45 impact on daily functioning and exclusion of alternative causes. First-line strategies comprise lifestyle and supportive measures, including patient education, behavioral strategies and exercise. If symptoms persist, treatment may be escalated to hormonal agents, such as elinzanetant or fezolinetant. Other parallel treatment options include non-hormonal agents such as SSRIs, SNRIs, gabapentin or clonidine, with careful monitoring for side effects and potential drug interactions. Long-term management requires regular reassessment of VMS severity, treatment tolerability and adherence, timely therapeutic adjustments and continued patient education to maintain both symptom control and adherence to breast cancer therapy. Treatment duration depends on the symptom burden of the patient and modifications during endocrine therapy course are needed regularly. In OASIS-4, elinzanetant was administered for 52 weeks.35 As long-term follow-up is not yet available, the length of therapy should be discussed and individualized with each patient.

Conclusion

Neurokinin receptor antagonists represent a major advance in the non-hormonal management of VMS, providing effective and well-tolerated relief. For women with breast cancer, these agents may address a critical gap in supportive care. Beyond symptom reduction, their use has the potential to improve adherence to endocrine therapy by alleviating one of the most common causes of treatment discontinuation, thereby contributing to better survival outcomes and highlighting their broader clinical significance. Both fezolinetant and elinzanetant have demonstrated compelling efficacy for the treatment of moderate-to-severe VMS; however, further research is needed to establish their role, including head-to-head comparisons with existing nonhormonal therapies, dedicated trials in breast cancer populations and rigorous long-term safety evaluation. Addressing these evidence gaps will be essential to support their integration into standard survivorship care pathways for women with HR-positive breast cancer.

Conflict of interest

Michael Gnant reports receiving personal fees and/or travel support from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, EPG Health (IQVIA), Menarini-Stemline, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre and Veracyte; he also holds leadership roles at ABCSG GmbH and ABCSG Research Services GmbH. Marcus Vetter received honoraria for consultancy from GSK, Roche, Novartis, ExactSciences, Pfizer, Stemline, AbbVie and ASC Oncology. Petra Stute serves on advisory boards for Astellas and Bayer and gives lectures at congresses supported by these companies. These funding entities did not play a role in the development of the manuscript and did not influence its content in any way.

Funding

The authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Author contributions

The authors created and approved the final manuscript.

_in_women_with_breast_c.png)

_in_women_with_breast_c.png)