Introduction

The diagnosis of myelodysplastic neoplasms (MDS) begins with cytomorphological evaluation of the peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM). More than 80 years ago, Maxwell Myer Wintrobe established the modern role of the hematology laboratory as the foundation of clinical diagnostics.1,2 Even earlier, in 1908, Giovanni Ghedini was the first to underline the diagnostic value of assessing PB together with BM and highlighted the importance of examining both aspirates and biopsy in context.3

These principles were carried forward into subsequent classification. In the French-American-British (FAB) classification (1976) and the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissue tumors (1999, 2008, 2016), the core diagnostic criteria for MDS remained consistent: cytopenias, blast percentage and dysplastic changes in at least one cell line.4–6 Among these, blast percentage has long been central to optimal morphological diagnosis, disease subclassification, prognosis and assessment of progression.

With the most recent classifications of hematological malignancies, the International Consensus Classification (ICC) and the 5th edition of WHO classification, diagnostic and prognostic subtypes are now primarily defined by molecular testing and next generation sequencing.7,8 However, blast count and dysplastic changes remain the integral part of the initial work-up in MDS diagnosis, guiding prognosis and therapeutic decision-making as well as the selection of appropriate therapy.9

This article provides an overview of the evolving diagnostic landscape of MDS, with a focus on morphological evaluation, technical pitfalls and the integration of digital and artificial intelligence (AI)-based tools.

Pitfalls in the initial diagnostic work-up of suspected MDS

The distinct morphological characteristics observed under an optical microscope, together with the method’s immediate availability and cost-effectiveness, allow for the timely identification of patients who may require further diagnostic investigations. Nevertheless, several challenges limit the diagnostic reliability of morphology. These include the lack of standardized preparation and staining techniques for PB and BM smears, the absence of a universally accepted nomenclature for blood cells and the inherent subjectivity linked to individual skills and experience.10 Collectively, these factors contribute to intra- and inter-operator variability, limiting the diagnostic value of morphology.

Another concern is the decline in training in classical morphology, particularly among younger colleagues.11–19 Many are less familiar with established recommendations and guidelines in the pre-analytic preparation and evaluation of PB and BM samples.20,21 This lack of experience and knowledge may also extend to the critical interpretation of other malignant and non-malignant diseases that may mimic MDS, such as other causes of cytopenias and dysplastic changes.19

Adequate pre-analytic work-up of peripheral blood and bone marrow

For harmonization and comparability of clinical trial data, strict adherence to WHO recommendations is essential. Adequate sampling is critical: cytogenetic analyses require material sufficient to evaluate at least 20 metaphases, and immunophenotyping also demands appropriate sample quantity.6 For a definitive diagnosis of MDS, WHO guidelines specify that a BM biopsy must include at least 1.5 cm core with 10 or more partially preserved intertrabecular spaces. These requirements ensure that the specimen is representative, allowing reliable assessment of marrow architecture, cellularity, fibrosis and the presence of abnormal cells, all of which are crucial for accurate diagnosis.

Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy: Technical considerations

BM evaluation often relies on films prepared from crushed marrow fragments, with wedge-spread films less frequently obtained. However, wedge-spread films are better for evaluating the granularity of neutrophils (which also should always be evaluated together with PB). Notably, the International Council for Standardization in Haematology (ICSH) recommends preparing both wedge-spread films and squash preparations.13 These should be stained with a Romanowsky stain, either May-Grünwald-Giemsa (MGG)22 or Wright-Giemsa.23 In addition, a blood count and peripheral smear should be obtained if not performed within the previous two days.

Either the aspirate or trephine biopsy may be performed first. If the aspirate is obtained first, the trephine biopsy should be taken through the same incision but positioned 0.5–1 cm away to avoid hemorrhagic or damaged cores.13 Conversely, if the biopsy is performed first, the aspirate needle should be placed on the bone surface approximately 0.5–1 cm away from the biopsy site to prevent clotting of the aspirate. Aspirate and trephine biopsy should be obtained using their respective needles. Using a trephine needle for aspiration poses a risk of hemodilution; if the biopsy is performed using the same needle, the trephine core may be damaged or hemorrhagic.

The length of the BM biopsy (i.e., the length of the core sample) is a key quality parameter: longer cores improve diagnostic and staging accuracy in hematologic disorders. While recommendations vary, a minimum of 15 mm is generally recommended for general assessment and a minimum of 20 mm for conditions such as lymphoma. Adequate length is crucial, as poor-quality biopsies with suboptimal length can hinder interpretation and necessitate repeat procedures, causing patient anxiety and delaying treatment. At least six smears and two particle squash (“crush”) slide preparations should be made. For squashes, a drop of BM containing particles is placed in the middle of one slide, overlaid with a second slide. The weight of the second slide on the first is sufficient to squash the marrow particles, and no downward force should be applied to preserve cellular detail. The slides are drawn apart from each other, in the direction of the long axis of the slide.

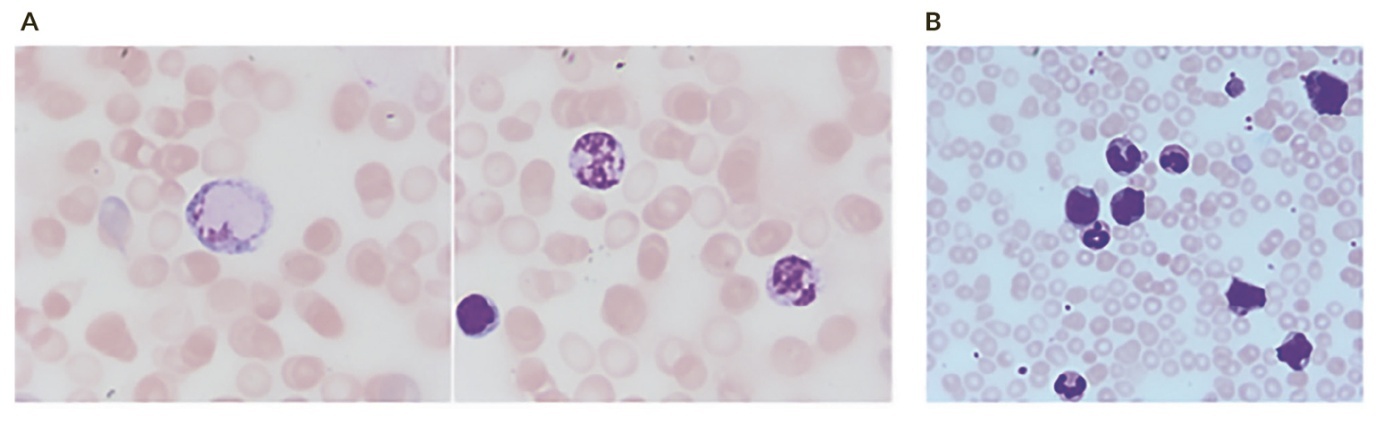

Coverslipping protects the slide from damage and creates a clear surface for microscopic examination. For PB smears, it can lead to a more even dispersion of blood cells, particularly leukocytes, resulting in a more accurate differential count. After a longer time of storage, PB which was coverslipped still shows preserved leukocytes which are often dissolved without it (Figure 1). For BM smears, coverslipping protects the delicate cell structure and ensures that the entire sample is visible for the assessment of cellularity and cell morphology.

Coverslipping a pre-prepared stained smear requires careful placement of the mounting medium and coverslip to avoid bubbles and ensure that the specimen is protected. Gently place a coverslip at a 45-degree angle to the slide, with one edge touching the mounting. It is important that the smears are dried completely. The time for this can vary and may take from several hours to overnight at room temperature.20,21,24–26

Data showed that BM collection with the help of trained laboratory technicians on-site yielded higher-quality specimens compared with unassisted procedures, particularly for aspirate smears (p<0.0001) and touch imprints (p<0.0001).27 Notably, the quality of aspirate smears was improved, which is important for cytologic evaluation. It provides a clearer view of cellular detail and architecture than a liquid BM aspirate, especially when the aspirate yields a “dry tap.” This technique is useful for evaluating BM pathologies, making an initial diagnosis, assessing cytological details and determining the possible presence of metastatic tumors. Touch preparations can even reveal more neoplastic cells than aspirates and may detect BM infiltration missed in aspirates, for example, in hairy cell leukemia, multiple myeloma or lymphoma.28

Artefacts and diagnostic pitfalls

Artifacts introduced during specimen handling can mimic or obscure true dysplasia. In 2001, Wang and Glasser demonstrated that storage of BM aspirates in EDTA induces dyserythropoietic changes.17 Even in patients without myelodysplasia, nuclear and cytoplasmic abnormalities resembling MDS features increased progressively when samples were stored at room temperature, evident as early as day one. However, refrigeration significantly reduced this effect.

Further evidence shows that excessive EDTA concentrations can induce progressive nuclear and cytoplasmic contraction, membrane damage, cell smudging and pyknotic nuclei.29 These changes may mimic hallmark dysplastic features such as hypolobated or small neutrophils and micromegakaryocytes. To minimize such artifacts, BM aspirates should always be collected in tubes containing the appropriate EDTA concentration. The optimal concentration for EDTA in BM aspirate is approximately 1.5 mg (+/- 0.25 mg) of dipotassium EDTA per 1 mL of blood, similar to PB samples.20 A common method is to add a small, proportional amount of BM (0.5–1.0 mL) to a tube containing pre-shaken-out excess EDTA solution to prevent dilution and clotting, as excessive EDTA can lead to poor staining. For molecular analyses, it is crucial to follow specific laboratory protocols, as different fixation and decalcification methods can affect the results. While the ICSH guidelines recommend to avoid EDTA if possible, another group did not find an advantage of not using anticoagulated BM while also showing that the best results were obtained with laboratory personnel at the bedside to assess sample quality and immediately perform slide preparation.30

Processing artifacts in BM aspirates can arise from improper drying of the film, prolonged storage and poor fixation and staining. Inadequate drying before fixation may cause nuclear contents to appear as if leaking into the cytoplasm, with indistinctive cellular borders. Water contamination in methanol used for fixation can cause refractile “inclusions” in red cells and disguise details. Delayed fixation and staining of archival BM slides produce a strong blue or turquoise tint, which is preventable by fixing before storage, although this may limit subsequent use. It is also important to ensure that slides are properly stained; otherwise, cells cannot be distinguished adequately and/or show artificially dysplastic changes (Figure 2). Inadequately stained slides are often encountered in hypercellular BM which was not dried long enough and or the staining solution was already too old or used for too many BM slides. I recommend changing the staining solution after 1–2 days or after having stained more than 20 BM slides (even earlier with very fatty BM).

Clotted aspirates may produce small marrow clots that resemble particles. This can be misinterpreted as true marrow fragments for assessment of cellularity or the presence of iron stores. The presence of fibrin strands and lack of organized structure of the apparent particle help distinguish them.

Interpretation should always be cautious. Dysplastic features in the BM of severely ill patients may reflect reactive changes rather than MDS. Similarly, chemotherapy-related dysplastic changes must be differentiated from therapy-induced MDS: the former resolve following withdrawal of the drug, whereas the latter persist. Therefore, a diagnosis of MDS should always integrate clinical, hematological, histological and genetic data rather than relying solely on the observation of dysplasia.

Role of bone marrow biopsies in MDS diagnosis

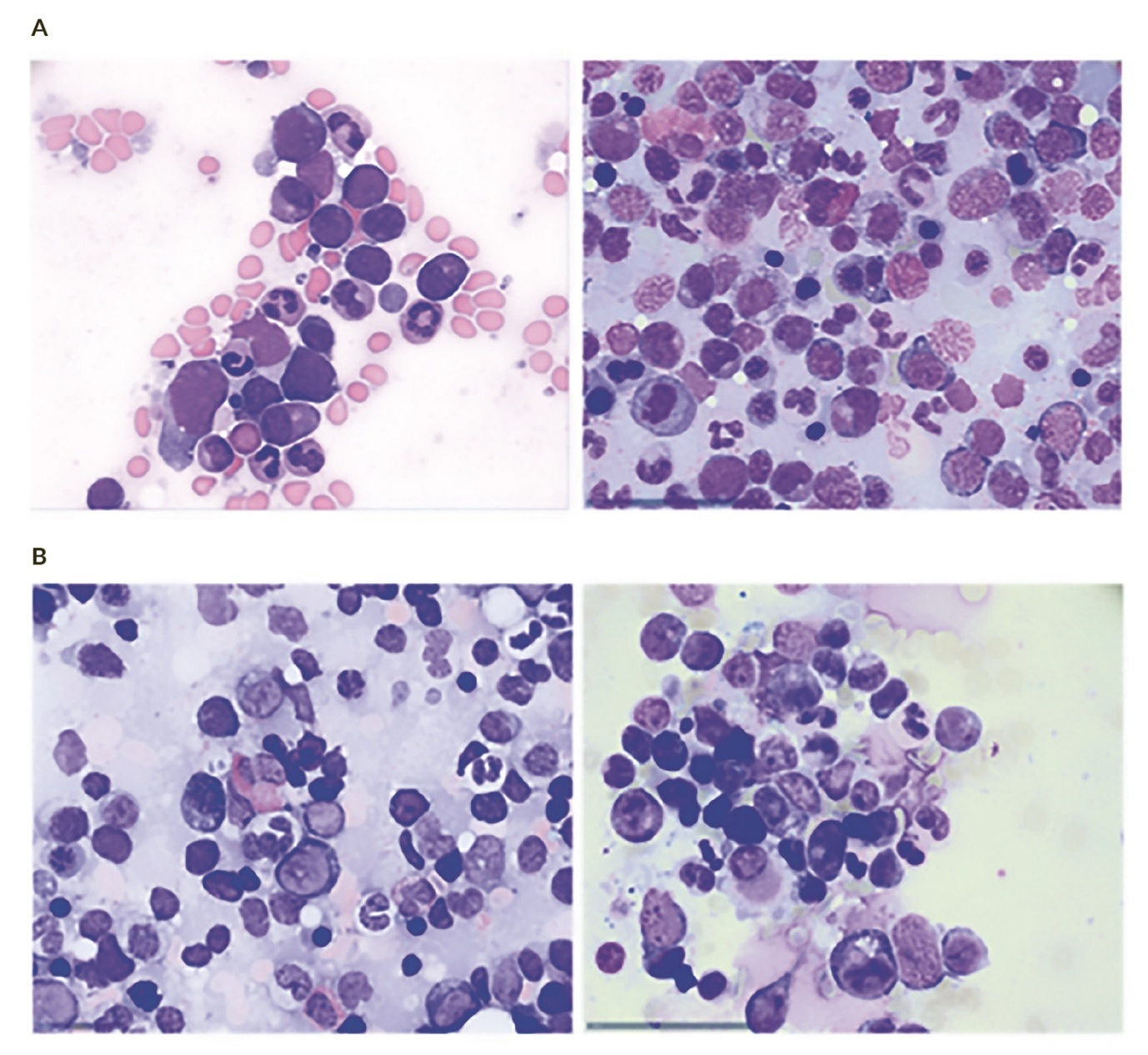

Bone marrow biopsies (BMB) play a central role in the diagnosis, classification and prognostication of MDS. In contrast to aspirates, the biopsy provides an architectural overview, allowing the assessment of cellularity, topography, fibrosis and dysplasia across lineages. This is essential in cases with heterogeneous blast distribution, fibrosis, or sticky (CD56+) blasts, where aspirate smears may be misleading or suboptimal.31

Diagnostic contributions

-

Assessment of cellularity:

BMB provides a reliable measure of marrow cellularity, which may range from hypo- to hypercellular in MDS, often discordant with peripheral cytopenias.

-

Identification of dysplasia:

The evaluation of dysplasia in the erythroid, granulocytic and megakaryocytic lineages is a cornerstone of diagnosis. Megakaryocytic dysplasia, in particular, can be observed by aspirate and BMB, revealing micromegakaryocytes, nuclear hypolobation, or clustering. While cytology can identify cellular atypia, biopsy can also assess distribution and grouping of atypical megakaryocytes. A disadvantage of BMB is the lack of efficient identification of dysplastic granulocytes and erythroid precursors. In particular, pseudo-Pelger cells, erythroid dysplasia and ring sideroblasts are readily identified by cytomorphology but are almost impossible to identify using BMB alone.

-

Blast quantification:

The proportion and distribution of blasts are key factors in distinguishing MDS from acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Biopsies may show patchy or focal blast clusters that are not apparent on aspirate smears, particularly in hypocellular or fibrotic marrows.

-

Evaluation of fibrosis:

Reticulin and trichrome staining of the BMB identifies the extent of marrow fibrosis by quantifying reticulin and collagen fibres, which carries independent prognostic significance in MDS.

-

Exclusion of other diseases:

BMB allows differentiation from conditions that can also be associated with fibrosis, including metastatic carcinoma, granulomatous diseases and also certain types of therapy-related marrow injury or vascular changes.

Artifacts, pitfalls and limitations of BMB

-

Sampling error:

Marrow changes in MDS are often focal, and a single biopsy may not represent the entire hematopoietic compartment. -

Blast count discrepancies:

Differences between aspirate and biopsy counts can occur; aspirate smear can show false low counts due to BM fibrosis or hemodilution. Biopsies may overestimate blast percentages when the BM sample is too small and blasts are focal or includes areas of cortical bone or soft tissue, giving a false impression of sufficient sampling. A minimum length of 15 mm is required macroscopically. The biopsy should not only contain subcortical BM areas, as here, cellularity can be falsely low and blast counting artificially low. -

Interpretive subjectivity:

Dysplasia grading can be observer-dependent, especially in borderline cases or post-therapy marrows. -

Fibrotic marrows (MDS-F):

Fibrosis may obscure morphology and mimic primary myelofibrosis. The blast count in the bone aspirate can be falsely low due to insufficient aspiration of blasts and accurately high using immunohistochemistry in BMB.

-

Sticky (CD56+) blasts:

CD56 expression can cause poor dispersion on aspirate smears, leading to underestimation of blasts. BMB is less prone to give false estimates, if the trephine is sufficient in length and immunohistochemistry including markers such as CD56 in combination with nuclear morphology or classic markers such as CD34 and CD117.31,32

-

Blast heterogeneity:

Uneven blast distribution in patchy marrows contributes to sampling bias and challenges prognostic stratification. This could affect both the aspirate and biopsy blast count and this error is addressed if both methods are used.

Digital pathology and artificial intelligence

Morphological analysis of blood cells remains a cornerstone of hematological diagnostics. Traditional assessment by manual light microscopy, still considered as the gold standard, is labor-intensive, requires continuous training and is susceptible to interobserver variability.

Digital morphology analyzers, supported by advances in imaging and AI, now provide automated pre-classification of cells, faster reviews and opportunities for remote consultation, archiving and training.33,34 These systems reduce visual fatigue, improve efficiency, facilitate networking between laboratories and support quality assurance and education.

Devices such as CellaVision accurately identify common white blood cell types and red cell morphology but are less reliable for rare or pathological cells, including blasts, plasma cells, schistocytes and immature granulocytes.33 Their performance may also be reduced in pediatric or leukopenic samples. Approximately 10–20% of challenging cases, particularly those with suspected dysplasia, intracellular parasites or platelet clumps, still require expert review. Thus, skilled morphologists remain essential for validation and interpretation.

Recent advances have introduced AI-driven digital microscopy systems into hematology laboratories, which provide automated morphological analysis of PB cells. Unlike flow cytometry (FC), which relies on physical-chemical parameters, these systems digitally transform stained smears and classify cells based on measurable morphological features such as size, contour, texture and color. Zini et al. (2023) evaluated the Mindray MC-80, an AI-based digital morphology analyzer, on 600 blood samples enriched with pathological cells.34 The analyzer showed excellent reproducibility (correlation coefficients >0.94), high sensitivity for immature granulocytes (98.8%) and nucleated red blood cells (97.5%), and over 80% pass rates for pathological cells. Although performance was weaker for reactive lymphocytes and lymphoma cells, overall results were comparable to expert microscopy.

Digital morphology has also been extended to BM aspirates.35 A recent study using whole-slide imaging (Metafer4 VSlide) showed quantitative and qualitative results comparable to conventional microscopy, with reliable detection of dysplastic features and no loss of diagnostic quality. Benefits included workload reduction, reproducibility, image preservation and easier data sharing.

In summary, digital and AI-based morphology analyzers now approach the performance close to expert microscopy, with clear benefits in efficiency, reproducibility and accessibility. Although expert oversight remains essential for rare or complex findings, these tools are increasingly becoming an integral part of modern hematology practice.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning

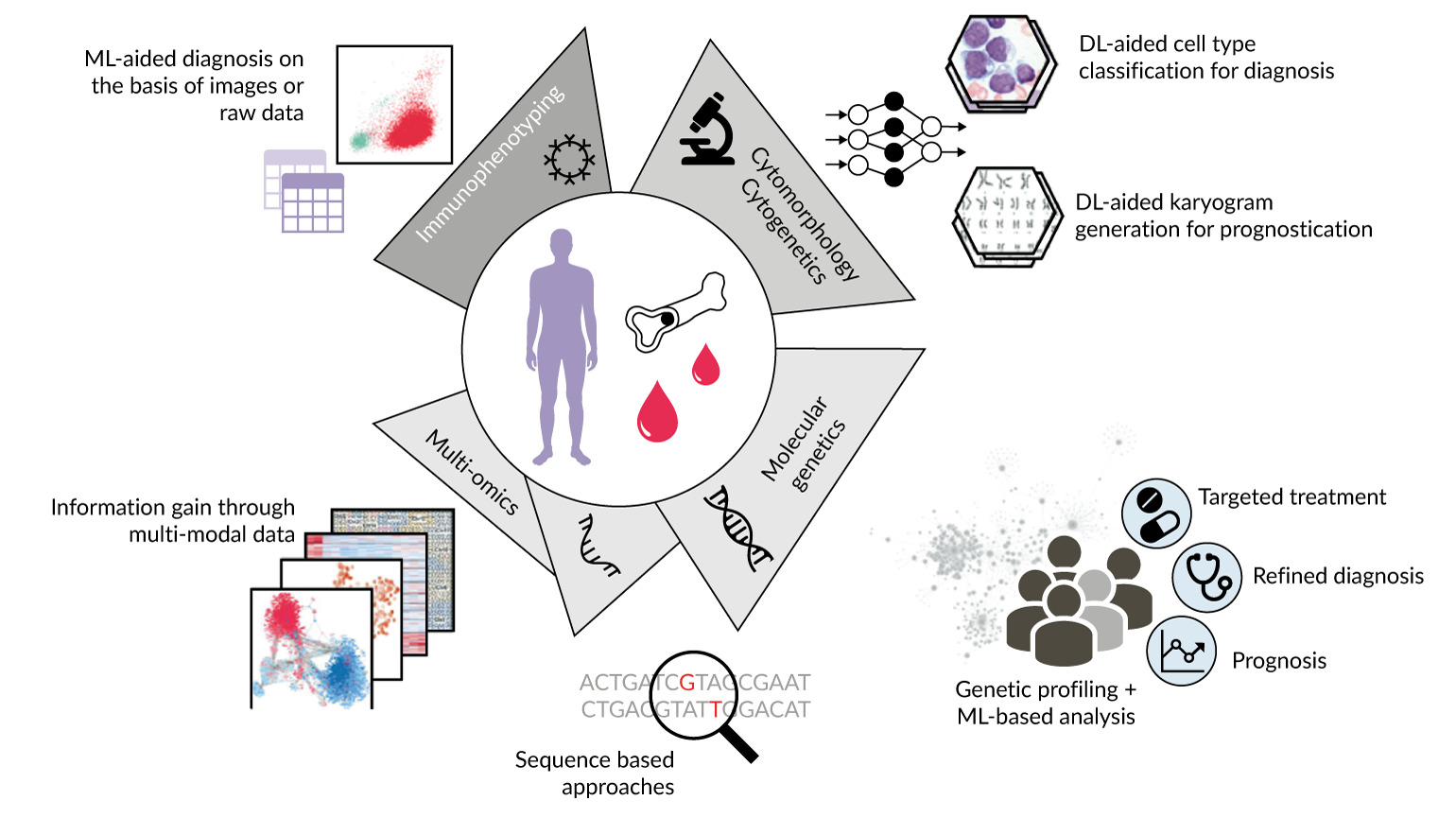

AI and ML are transforming modern hematology by streamlining diagnostics and supporting clinical decision-making.36–38 These technologies improve efficiency, accuracy and patient outcomes by automating tasks that traditionally rely on expert interpretation.39 In digital morphology, ML has been applied to classify white and red blood cells, detect dysplasia and differentiate between disorders such as MDS and aplastic anemia (AA). Beyond morphology, AI assists in cytomorphology, multicolor FC interpretation, karyotyping, genetic variant analysis and genomic profiling (Figure 3).

Over recent years, AI/ML have been applied to the three main diagnostic modalities for MDS: BM samples, PB smears and FC.40 In BM analysis, deep learning models have shown strong potential in classifying blasts, predicting relapse risk and identifying pediatric leukemias. AI has been developed to detect dysplastic cells and quantify blasts, which are crucial for MDS diagnosis but often challenging for pathologists. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) demonstrated good performance in recognizing dysplasia across multiple lineages, although blast quantification remains limited.41 AI can also distinguish between MDS, AA and AML, which share clinical features such as cytopenia but differ in prognosis and treatment.42 A CNN trained on the ASH Image Bank and validated with clinical data achieved impressive accuracy: an AUC of 0.985 for a two-class MDS model and 0.968 for a three-class AA/MDS/AML model, with validation confirming robust performance and rapid image processing (0.3 s). While larger datasets and subtype analyses are needed, these results highlighted the feasibility of integrating AI into clinical hematology.

When applied to PB smears, AI reduces subjectivity in assessing morphological abnormalities. Models trained to detect hypogranulated neutrophils have shown high accuracy and sensitivity,40 while large CNN-based systems distinguished MDS from AA with strong diagnostic performance.43 ML approaches integrating complete blood count data with novel parameters, such as immature platelet fraction, have further improved predictive power and improved existing scoring systems.44 These methods improve efficiency, limit the need for extensive smear review and introduce greater objectivity. However, limitations remain, including restricted validation cohorts and unresolved economic considerations.

FC has also seen major advances through ML, particularly in automating gating, subclassifying leukemias and lymphomas and detecting minimal residual disease.39,40 ML algorithms applied to multiparametric FC data have outperformed traditional systems such as the Ogata score, with robust sensitivity and specificity across different instruments and centers.45,46 The (extended) Ogata score is a FL-based scoring system for diagnosing MDS that evaluates four parameters (in the extended Ogata Score one extra point was added for the expression of CD7 on myeloid progenitors with a threshold of 20% or of CD56 on monocytes, with a threshold of 30% positive cells): percentage of myeloid precursors, frequency of B-cell precursors, CD45 antigen expression ratio and neutrophil granularity (SSC) ratio. Its strengths include its technical simplicity, international impact and ability to distinguish MDS from reactive conditions with high specificity, whereas its main weakness is limited sensitivity in low-grade MDS and a tendency to have false positives in other conditions like iron deficiency and toxic effects, e.g. due to methotrexate, making it a useful but supplementary tool requiring clinical context.47,48

Novel approaches, including real-time deformability cytometry combined with ML, can also distinguish MDS from healthy controls by capturing mechanical and morphological cell characteristics. Furthermore, deep learning models have also classified MDS versus AML and normal samples with high accuracy.49

AI is also advancing molecular genetics and cytogenetics. Algorithms now support variant calling, risk stratification, treatment prediction and integration of multi-omics data into diagnostic and prognostic models (Figure 3).39 However, attention should be paid to the limitations of automatic variant calling. Many current technologies can miss important variants with low variant allele frequency (VAF), meaning these tools are not yet ready for routine clinical use without expert human oversight. Similarly, in cytogenetics, automated karyotyping combined with deep learning shows promise in the detection of numerical and, to a lesser extent, structural abnormalities. These remain more challenging due to limited training material and the heterogeneity of alterations.

Limitations

Despite the remarkable promise of AI in hematologic diagnostics, significant barriers remain.38 Many studies are limited by small, disease-specific datasets, lack of diversity and insufficient external validation, which all increase the risk of bias and poor generalizability, particularly for rare hematologic subtypes.38,40 Variability in staining protocols, instrumentation and data quality across laboratories further complicates reproducibility. Another major concern is explainability: opaque “black box” models may undermine clinician trust and hinder clinical adoption. Advances in explainable AI, which clarifies outputs and may identify new digital biomarkers linking genotype and phenotype, are therefore critical for safe integration.

Ethical and regulatory issues also persist, including data protection, accountability for errors and potential erosion of the doctor-patient relationship if AI systems are misused.37 The evolving nature of algorithms raises additional challenges for oversight and highlight the need for frameworks such as the EU AI Act to balance innovation with patient safety.38

Education is another key priority. Without AI literacy, clinicians may misinterpret outputs, even when technically accurate. AI trainings should therefore be integrated across all levels: in undergraduate education, applied use during residency and advanced instructions in ethics, communication and clinical oversight during specialist training.37

Conclusions

Blood cell evaluation by optical microscopy remains the reference method for the quantitative and qualitative analysis of hematological cells on PB and BM smears. However, the lack of financial incentives for cytomorphology and the long, time-intensive training required to gain expertise have led to increasing outsourcing of these diagnostic tasks, especially in smaller hospitals. As a result, younger physicians often have fewer opportunities to improve their skills in the initial work-up of cytopenias, potentially delaying diagnosis of MDS or even acute leukemias. Furthermore, laboratories outside the treating institutions may lack clinical and laboratory information, which can complicate the interpretation of PB and BM findings. In interpreting cytopenias as well dyspoietic changes, it is also important to be aware of other common causes like vitamin B12 deficiency,50 toxic effects of drugs, inflammation and chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms, especially those with myelofibrosis. MDS evaluation should also not be performed in patients receiving erythropoiesis-stimulating factors or G-CSF.48

In patients with “MDS with low blasts” mainly diagnosed by dysplastic changes, follow-up is necessary to exclude reactive changes in the background when blood counts normalize over time, which confirms that dysplasic changes (especially megaloblastoid erythropoiesis) are not specific for MDS and therefore follow-up is absolutely necessary.51,52 Blast count assessment in the PB, aspirate smear and BMB are equally important. The highest blast count defines the blast count needed to render the correct diagnosis, which also integrates the cytogenetic and molecular findings. Recognizing artifacts and interpretive pitfalls of BM aspirate and biopsy interpretation is essential for diagnostic accuracy and risk stratification. Integrative hematopathology and communication among all laboratory specialists enable rapid and accurate classification and timely therapy.

Advances in AI technology offer new opportunities to support morphology. Commercial AI systems may facilitate consultation, remote review, rapid cell image retrieval, reduction of fatigue (since optical microscopy is physically demanding), cost savings and improved intra- and inter-laboratory training, harmonization and peer review.39,40 However, limitations must be acknowledged. AI systems may overlook rare or diagnostically challenging cells, especially if scanning is selective or restricted to certain areas of the smear.38 Overreliance on “black-box” deep learning models may also reduce interpretability and limit the ability to recognize unexpected morphological details. These limitations have already been highlighted in recommendations by the ICSH.33–40,42,53

Conflict of interest

The author has declared that the manuscript was written in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

The author has declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Author contributions

The author has created and approved the final manuscript.