The evolving treatment landscape for R/R DLBCL

Large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) is the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), accounting for approximately 30–40% of them.1,2 It is an aggressive form of NHL, with 5-year survival rates ranging from 55% to 80%.3 In Switzerland, the annual incidence of LBCL is approximately 5 per 100,000 people, equating to nearly 450 new cases each year.4 Despite many patients presenting with advanced disease, approximately two-thirds achieve remission with the standard first-line chemotherapy regimen of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP). However, while frontline R-CHOP is effective, up to 30% of patients either do not respond or experience relapse, typically within the first two years.5–8 Consequently, most patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) LBCL represent a significant therapeutic challenge. The prognosis of R/R LBCL patients is poor, although some individuals achieve long-lasting remission and might even be cured with second-line therapies.8 Nevertheless, R-CHOP and subsequent chemoimmunotherapy might cause long-term toxicities, including cardiotoxicity and neuropathy.9 They may also facilitate infectious events in frail patients. As LBCL primarily affects older individuals, with a median onset age of 70 years, patients with pre-existing heart conditions are especially vulnerable to the toxic effects of anthracycline-based therapies and, therefore, reduced intensity regimens have been proposed for frail patients.10

Until the advent of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell immunotherapy, the standard of care (SoC) treatment for fit patients with R/R LBCL was salvage chemotherapy followed by a high-dose chemotherapy conditioning scheme and autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT).8 However, approximately 50% of patients with LBCL are ineligible for transplant, and the majority of patients who undergo ASCT eventually relapse, leaving them with few treatment options.11 Moreover, patients who are primarily refractory or relapse within a year of receiving rituximab-based first-line treatment respond poorly to standard salvage chemoimmunotherapy, due to the chemo-resistant characteristics of their disease.12

Finally, multiple exposure to DNA-damaging agents, including chemotherapy and radiotherapy, is associated with the emergence of second primary myeloid neoplasia over the follow-up, characterized by an adverse prognosis.13–17 The mutagenic effect of exposure to DNA-damaging therapies might lead to the emergence of second primary neoplasms, even after later non-DNA-damaging treatments such as CAR T-cell immunotherapies.18 These limitations highlight the need for more personalized, effective, and less toxic treatment options for LBCL patients.

In recent years, a better understanding of the epidemiology, prognostic factors, and heterogeneity of LBCL has refined disease classification and led to the development of novel therapies. CAR T-cell immunotherapy has emerged as the new SoC for R/R DLBCL.8,19 Over the past decade, three anti-CD19 CAR T-cell products have been approved for adult LBCL patients who have received two or more lines of systemic therapy: axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel), tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel), and lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel) (Table 1). Axi-cel and tisa-cel were first approved for clinical use after at least two lines of therapy by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and Swissmedic in 2018, based on the pivotal phase II ZUMA-120 and JULIET21 trials, respectively. Liso-cel received FDA approval in 2021 and was later approved by Swissmedic and EMA in 2022, primarily based on the TRANSCEND-NHL-001 trial,22 which demonstrated significant improvements in response rates and survival outcomes compared with standard treatments in patients with R/R LBCL. Several novel therapies are currently in development, including rapcabtagene autoleucel, relmacabtagene autoleucel, and GLPG5101 (Table 1).

CAR T-cell immunotherapy is the new standard of care in second-line settings

The indications for axi-cel and liso-cel were further expanded to include second-line treatment for patients with LBCL who relapse within 12 months of completing, or are refractory to, the first-line of anthracycline-containing chemoimmunotherapy. These approvals were supported by the positive results from the phase III ZUMA-723 and TRANSFORM24 clinical trials. A third phase III clinical trial, BELINDA, did not demonstrate a significant event-free survival (EFS) benefit for tisa-cel compared with standard therapy in LBCL patients who were refractory to or progressed within 12 months of first-line therapy.25 For this reason, tisa-cel is not approved as a second line of treatment in LBCL.

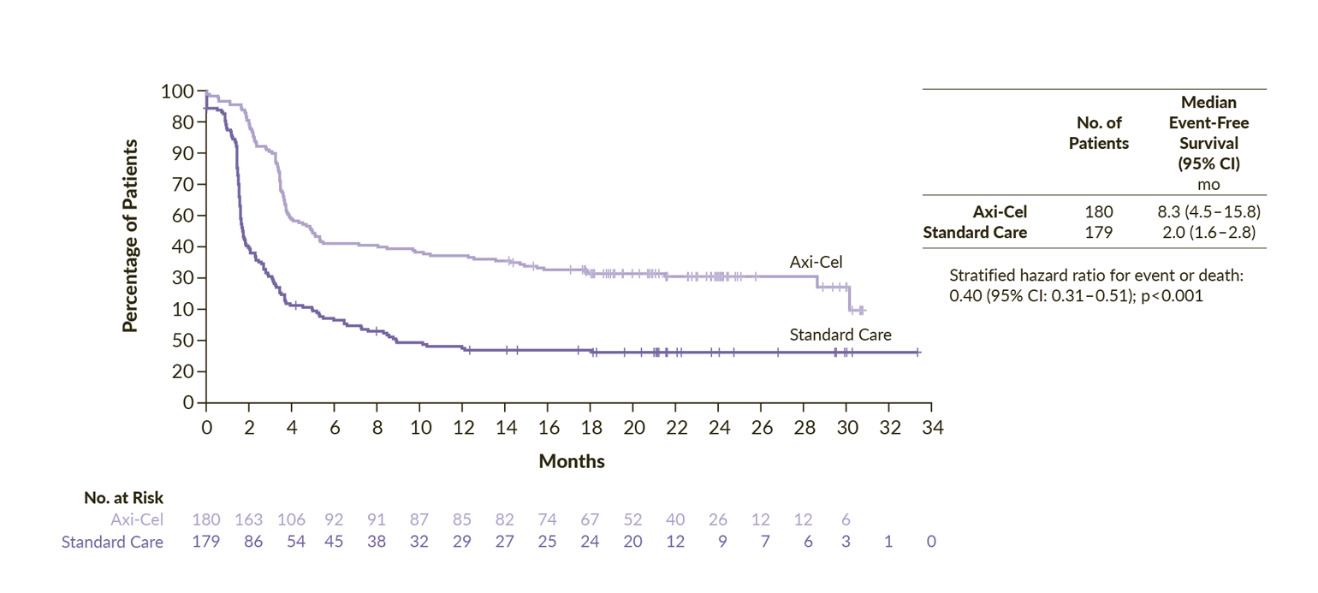

The phase III ZUMA-7 study was an open-label, multicenter trial comparing second-line axi-cel with salvage chemotherapy and high-dose therapy with ASCT (SoC) in patients with LBCL refractory or relapsed within 1 year from a first-line of anthracycline-containing chemotherapy regimen.23 The primary endpoint of the study was met. The median EFS was 8.3 months for axi-cel and 2.0 months for SoC and 24-month EFS rates were 41% and 16%, respectively (HR: 0.40 [95% CI: 0.31–0.51]; p<0.001) (Figure 1). Overall response occurred in 83% of the patients treated with axi-cel and 50% in the SoC arm, with a complete response (CR) in 65% and 32%, respectively. Axi-cel also demonstrated an overall survival (OS) benefit compared with SoC. At a median follow-up of 47.2 months, the median OS was not reached in the axi-cel arm and it was 31.1 months in the SoC arm (HR: 0.73 [95% CI: 0.54–0.98]; p=0.003).26 The risk of death was reduced by 27%, although 57% of patients in the SoC arm received subsequent cellular immunotherapy. The persistent long-term duration suggests the potential for curative treatment. Notably, this was the first trial in nearly three decades in the second-line setting to demonstrate a significant improvement in OS in LBCL. Finally, a post hoc analysis censoring survival at the time of subsequent CAR T-cell treatment in patients randomized to the SoC arm, highlighted that receiving axi-cel in second-line prolonged OS compared to receiving it as a third or later line of treatment. Indeed, this OS advantage suggests that an upfront treatment with CAR T-cell immunotherapy might be more effective than receiving it in a later-line-of-therapy setting. However, as a notable mention, the ZUMA-7 trial did not allow any bridging therapy in the axi-cel arm, and this might have led to a selection of patients with less aggressive disease. Finally, patients in the SoC arm who went on to receive third-line cellular immunotherapy achieved improved progression-free survival (PFS) and OS outcomes compared with those who did not.23,27 Specifically, the median PFS was 6.3 months and median OS was 16.3 months for patients who received third-line cellular immunotherapy, while the median PFS and median OS were 1.9 months and 9.5 months for patients who received other therapies in the third-line setting. These findings, along with the improved survival outcomes observed following stem cell transplantation after salvage chemotherapy or third-line therapy, underscore the importance of comprehensive treatment planning in the management of LBCL.

The phase II ALYCANTE trial was the first study to evaluate axi-cel as a second-line treatment in 62 patients with LBCL who were ineligible for intensive chemotherapy and ASCT.28 The trial met its primary endpoint, with a CR rate of 71% at three months, compared with the expected 12% with SoC. The median PFS was 11.8 months and the median OS was not reached. Axi-cel was well tolerated in patients considered unfit for high-dose treatments. These findings complement the ZUMA-7 trial and reinforce the role of axi-cel as a second-line option for R/R DLBCL regardless of transplant eligibility.

The TRANSFORM study was a pivotal global phase III trial that compared liso-cel with salvage chemotherapy followed by ASCT (SoC) as a second-line treatment for transplant-eligible patients with primary refractory or early relapsed LBCL.24 At a median follow-up of 17.5 months, the median EFS was not reached in the liso-cel group, while it was 2.4 months for the SoC group (HR: 0.356 [95% CI: 0.243–0.522]; p<0.0001) (Figure 2).29 The 18-month EFS rates were 52.6% versus 20.8%, respectively. The CR rate in the liso-cel arm was 74% and 43% in the SoC arm, demonstrating the superiority of liso-cel over SoC. The median PFS was not reached for liso-cel compared with 6.2 months for SoC (HR: 0.400 [95% CI: 0.261–0.615]; p<0.0001), with 12-month PFS rates of 63.1% for liso-cel versus 31.2% for SoC. The median OS was also not reached among patients receiving liso-cel versus 29.9 months for those receiving SoC (HR: 0.724 [95% CI: 0.443–1.183]; p=0.0987). The OS rates at 12 months were 83.4% and 72.0%, respectively. Finally, in a pre-specified OS analysis, after the three-year follow-up, liso-cel continued to demonstrate sustained efficacy, with higher OS rates and a consistent safety profile, even when accounting for crossover patients who subsequently received liso-cel. The median OS was still not reached for liso-cel, and the 36-month OS rates were 63% for the liso-cel group and 52% for the SoC group.30

The phase II PILOT trial evaluated liso-cel in second-line for 61 patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma who were ineligible for intensive chemotherapy or ASCT. The primary endpoint was an advantage in the overall response rate (ORR) compared with the null hypothesis of 50.2% ORR based on a real-world cohort control. The 80% of the patients treated with liso-cel achieved overall response, with 54% of CR. The median PFS and OS were 9.03 months and not reached, respectively. Remarkably, the safety profile was manageable in this frail and unfit population. The results of this trial support liso-cel as a potential second-line treatment in LBCL patients not eligible for ASCT.31

Although no clinical trials have directly compared the two CAR T-cell therapies, their effectiveness and safety have been evaluated in several real-world studies. A single-center study comparing axi-cel and liso-cel as a second-line therapy in patients with LBCL included 99 patients treated with axi-cel and 50 with liso-cel.32 The best response at three months of CAR T-cell infusion indicated similar effectiveness between the two therapies. With a median follow-up of 27 months, the ORR was 77% for axi-cel and 76% for liso-cel (p=0.9), including CR rates of 48% and 49% (p>0.9), respectively. No significant difference between axi-cel and liso-cel was also reported for OS (median, 16 months in both groups; p=0.53) and PFS (median, 9.5 months vs 7.2 months, respectively; p=0.47), with 1-year OS rates of 55% versus 66% (p=0.29) and 1-year PFS rates of 40% versus 32% (p=0.43). Regarding safety, axi-cel was associated with a higher incidence of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) of any grade, occurring in 88.9% of patients compared with 64.0% for liso-cel (p>0.001). Any-grade immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) was observed in 52.6% of patients receiving axi-cel and 28.0% of those receiving liso-cel (p=0.004).32

Real-world studies have demonstrated that CAR T-cell immunotherapy is both effective and feasible for older patients, with outcomes comparable to those observed in younger patients. In a recent multicenter cohort study, no significant difference was reported between patients aged ≥70 years and those aged <70 years who received either axi-cel or lisa-cel in terms of ORR (78.3% vs 77.7%; p=0.63), PFS (median, 11.1 months vs 10.2 months; p=0.93), and OS (median, 34.4 months vs 21.8 months; p=0.97). These findings support the conclusion that age alone should not be a limiting factor in determining eligibility for CAR T-cell immunotherapy, as older patients can derive similar benefits.33 Geriatric assessment can be useful to identify patients who can benefit most from CAR T-cell immunotherapy, as demonstrated by Chihara et al. (2023).34 Therefore, treatment decisions should focus on the patient’s overall health status and suitability for the therapy, rather than chronological age.

Disease control at the time of CAR T-cell infusion improves treatment outcomes

A prespecified exploratory analysis of ZUMA-7 examined the association between pretreatment tumor characteristics and treatment outcomes with axi-cel versus SoC.35,36 High tumor burden, as measured by metabolic tumor volume (MTV), emerged as a negative prognostic factor for response durability across both treatment groups. Despite this, axi-cel maintained its therapeutic advantage over SoC in both high- and low-tumor burden cohorts, supporting its role as a second-line LBCL treatment. Importantly, patients with lower tumor burden experienced fewer adverse events, including grade ≥3 neurotoxicity or CRS, suggesting that tumor burden may influence the severity of treatment-related toxicity.23,36 These findings underscore the importance of evaluating prognostic factors such as MTV to better stratify patients for CAR T-cell immunotherapy and emphasize the need to standardize definitions and thresholds for tumor burden.36

Although CAR T-cell immunotherapies, such as axi-cel and liso-cel, have shown remarkable efficacy in R/R LBCL, including achieving CR in approximately one-third of patients, several challenges remain. Adverse events, such as CRS and neurotoxicity, as well as issues related to T-cell quality at the time of apheresis, continue to impact treatment outcomes.37 Grade ≥3 CRS and ICANS occur in approximately 15–25% and 10–30% of patients, respectively. Ongoing research aims to identify disease- and patient-specific factors that influence CAR T-cell immunotherapy response and safety.

The need for systemic bridging therapy between T-cell apheresis and CAR T-cell infusion, which is often indicative of a highly aggressive disease, has been associated with reduced OS, potentially representing a confounding factor related to the aggressiveness of the disease.38,39 A recent analysis prospectively investigated the role of bridging therapy in the CAR T-cell immunotherapy setting and demonstrated that patients who reduced tumor load due to bridging therapy improved their prognosis compared with patients who did not respond or progressed during bridging.40 These observations underscore the importance of disease control before CAR T-cell infusion. Effective pretreatment and treatment sequencing are critical for optimizing outcomes in patients with R/R LBCL.

Frontline CAR T-cell immunotherapy shows promise for high-risk DLBCL

An important observation from the pivotal ZUMA-1 trial was that patients who had received fewer prior lines of treatment tended to exhibit increased biological and clinical activity of CAR T cells.41 This observation supports the idea that earlier use of CAR T-cell immunotherapy may yield better outcomes compared to its use in later treatment lines. For these reasons, CAR T-cell immunotherapy is under investigation as a new strategy to intensify first-line therapy to effectively treat high-risk chemoresistant LBCL. Patients with high-risk LBCL, including lymphomas harboring MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements (also defined as double- or triple-hit lymphomas), high International Prognostic Index (IPI) and patients with persistent disease at interim positron emission tomography (PET) imaging have a poor prognosis when treated with standard first-line R-CHOP, with CR rates below 50%.42–44 Based on this rationale, the ZUMA-12, a prospective, phase II, multicenter, single-arm trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of axi-cel as part of first-line therapy following an incomplete regimen of two cycles of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and an anthracycline-containing chemoimmunotherapy.45 The trial included 40 patients with high-risk features, including double- or triple-hit status or IPI score ≥3. Remarkably, all the patients must have an interim PET after two cycles of systemic chemoimmunotherapy consistent with persistent disease.45 After a median follow-up of 47.0 months, high-risk LBCL patients treated with axi-cel as part of first-line therapy achieved a CR rate of 86% and an ORR of 92%. At this data cut-off, 73% of patients maintained an ongoing response, all of whom remained in CR. The median duration of response (DoR) was not reached, and the 36-month rate of ongoing response was 81.8% in the overall cohort and 84.4% in those who achieved a CR. Finally, the median EFS, PFS, and OS were not reached, with estimated 36-month survival rates of 73.0%, 75.1%, and 81.1%, respectively.46

Given the positive results of ZUMA-12, the role of axi-cel as a frontline therapy for patients with high-risk LBCL is under evaluation in the phase III, randomized controlled ZUMA-23 trial.47 This landmark study is designed to compare axi-cel to SoC in patients with high-risk LBCL. The trial aims to enrol approximately 300 adult patients with high-risk LBCL. All eligible patients will initially receive one cycle of rituximab-based chemotherapy, after which they will be randomized to receive either axi-cel or continue with SoC. The primary endpoint is EFS, with secondary endpoints including OS and PFS, as well as assessments of safety, quality of life, and pharmacokinetics. The trial is still recruiting and preliminary results are not being provided yet.

Biological rationale for upfront CAR T-cell immunotherapy treatment

Exposure to chemotherapeutic agents affects the cell metabolism of multiple organs, including T cells.48 Indeed, multiple lines of chemotherapy deteriorate T-cell metabolism and fitness, leading to a CAR T-cell product being less active.49 Biological evidence of this phenomenon has been explored in different translational studies. T cells harvested from patients with B-cell NHL who never received chemotherapy were enriched in naïve T cells compared with T cells obtained from patients already exposed to conventional chemotherapeutic regimens. Also, T cells from patients exposed to chemotherapy have upregulation of exhaustion markers (PD-1, LAG-3, TIM-3 and TIGIT), and gene expression and epigenetic modifications associated with reduced functionality. Moreover, CAR T cells manufactured from chemotherapy-exposed T cells demonstrated inferior killing activity compared with chemotherapy-naïve T cell-derived CAR T cells in vitro.50 Similar results have been reported in the setting of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia or solid neoplasm patients.51 Indeed, clinical evidence confirmed that exposure to multiple lines of therapy is a negative prognosticator of survival and disease response to CAR T-cell immunotherapy in LBCL,52,53 supporting the idea of moving CAR T-cell immunotherapy to earlier lines of treatment in order to ensure the optimal product activity.

Moreover, in patients who do not respond to treatment, exposure to different lines of chemotherapy selects resistant neoplastic clones harboring genetic lesions conferring a more aggressive behavior and making LBCL more difficult to treat with subsequent lines of therapy.54 Mutations or disruptions of TP53 confer resistance to chemotherapy in LBCL and are commonly observed in R/R diseases. TP53 mutations might be observed at diagnosis, but they can also be detected at disease relapse, suggesting that malignant clones harboring them have a selective advantage to resist chemotherapy treatment.54 Although CAR T-cell immunotherapy does not directly exert its anti-neoplastic activity by interacting with neoplastic DNA, patients with LBCL harboring TP53 alteration have reduced survival and chances to achieve a CR when treated with CAR T-cell immunotherapy. Indeed, TP53 alterations seem to alter transcriptomic expression of several genes in neoplastic cells, including genes involved in the granzyme B-perforin and cytokine-killing mediated pathways, conferring them resistance to CAR T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity.55 Therefore, an earlier use of CAR T-cell immunotherapy might reduce the selection of neoplastic clones harboring genetic lesions associated with reduced susceptibility to apoptosis and interferon-mediated toxicity.

Conclusions and future outlook

The future of CAR T-cell immunotherapy in treating relapsed aggressive lymphomas, including LBCL, is increasingly promising due to its potential for personalization and its adaptability to disease heterogeneity. As the limitations of standard treatment paradigms become more evident, there is a growing need for new algorithms that incorporate CAR T-cell immunotherapy earlier in the treatment process. Integrating this advanced therapy has the potential to redefine patient outcomes by enabling a more personalized approach that better aligns therapeutic decisions with predicted individual benefits and risks.

Beyond CAR T-cell therapy, several immunotherapeutic modalities are being explored in the earlier lines of LBCL treatment. Bispecific antibodies, such as glofitamab,56 epcoritamab57 and mosunetuzumab,58 have demonstrated potent antitumor activity in R/R LBCL, achieving high response rates with manageable toxicity profiles. Building on these results, several trials are evaluating bispecific antibodies in the frontline setting, with promising results. These include combinations of mosunetuzumab with R-CHOP,59 glofitamab with Pola-R-CHP or R-CHOP60 and epcoritamab with R-CHOP,61 reflecting the growing interest in introducing T-cell-redirecting therapies earlier in the treatment algorithm. These agents can be delivered off-the-shelf, offering logistical advantages over autologous CAR T-cell products. In addition, antibody-drug conjugates, such as polatuzumab vedotin,62 and small-molecule inhibitors targeting signaling pathways, such as Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK),63,64 continue to expand the treatment armamentarium. Comparatively, CAR T-cell therapy remains unique in its curative potential and durable responses, although the integration of other agents and sequencing approaches may further optimize outcomes in relapsed LBCL.

Apart from clinical efficacy, the earlier integration of CAR T-cell therapy into the LBCL treatment algorithm will require careful consideration of practical aspects, including manufacturing logistics, patient flow and toxicity management. Shortening the vein-to-vein time and optimizing patient referral pathways are essential to ensure timely access to therapy, especially for those with rapidly progressing disease. Additionally, early CAR T-cell use might shift the burden of monitoring and toxicity management toward centers with specific expertise. This underscores the importance of multidisciplinary coordination and early toxicity preparedness. Identifying optimal candidates for frontline CAR T-cell therapy will be key to maximizing its benefit while maintaining cost-effectiveness and safety. Aside from the inclusion criteria of ongoing trials, emerging translational data suggest that molecular and imaging biomarkers may guide this selection. Genetic lesions, such as MYC/BCL2/BCL6 rearrangements and TP53 mutations, as well as high metabolic tumor volume or persistent disease on interim PET scans, identify patients with inferior outcomes after R-CHOP who might benefit from early cellular immunotherapy.65–68 Incorporating such biological and functional markers into clinical decision-making could help define those most likely to achieve durable remission with upfront CAR T-cell therapy.

In summary, insights from ongoing and future randomized trials will be fundamental in refining frontline CAR T-cell strategies and optimizing the precision and effectiveness of the treatments for LBCL. This innovative approach holds the promise of significantly improving outcomes, particularly for patients most likely to benefit from early intervention with CAR T-cell immunotherapy.

Conflict of interest

GG worked as a consultant for ViTToria Biotherapeutics and Gilead & Kite.

Funding

The author has declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Author contributions

The author created and approved the final manuscript.

_versus_s.png)

_versus_s.png)