Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is an incurable hematologic neoplasia that affects plasma cells. It mostly affects older individuals, with a median age of 69 years and one-third of the patients being older than 75 years at the time of diagnosis. Its incidence increases with age. The growing aging of the population is anticipated to generate an 80% increase in MM patients aged more than 65 by 2030.1

Older patients represent a heterogeneous group in which the prevalence of frailty increases with age. It is highly important to identify those older patients with MM who are frailer and classify them into different frailty subgroups.

Frailty is defined as a decline in physiological function, which leads to dependency, vulnerability and a high risk of complications resulting in an increased risk of morbidity and mortality.2 Some studies show that severe frailty is present in at least 40% of MM patients.3

This frailty assessment is key to avoiding overtreatment, which could lead to toxicities and early discontinuation. Early mortality is also alarming in frail MM patients. This has been evidenced by some studies, such as the phase II HOVON 143 trial, which were specifically addressed to this patient population.4,5

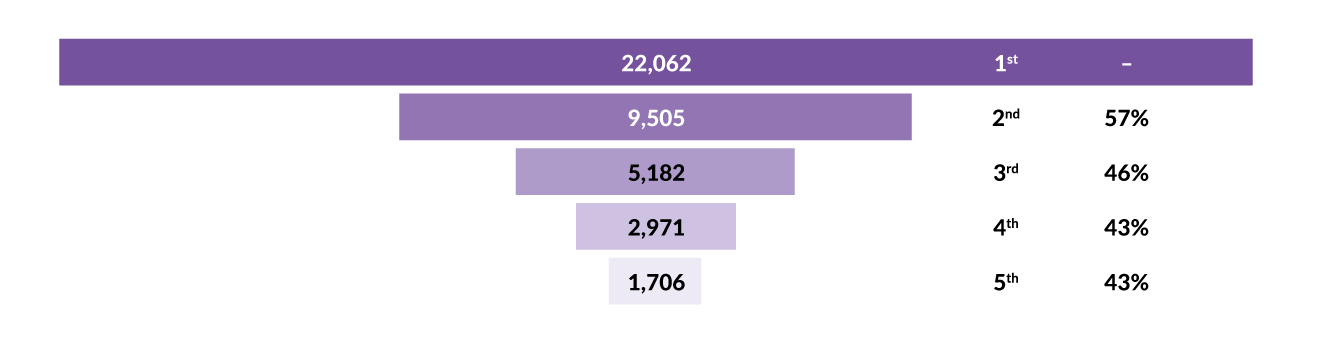

On the other hand, it is important not to undertreat the disease, as many elderly MM patients will receive only one line of therapy. Several retrospective real-world studies have shown a high rate of attrition by each line of therapy in myeloma (Figure 1).6 Only around 40% of transplant-ineligible patients reach the second line of treatment, and it is likely even worse in older and frail patients. For this reason, the most effective treatment should be administered in the first line in order to provide the patient with the best opportunity to obtain durable disease control and improved survival.

In this review, we will focus on the different frailty assessments available for MM and different treatment options for elderly patients, both in newly diagnosed and relapsed/refractory MM. We will also look into treatment perspectives for this group of patients.

MM in older patients: Definitions and assessment

Elderly MM: Definitions

In the literature on MM, we can differentiate between different terms when referring to the elderly population:

-

Transplant-ineligible patients: Patients considered not fit enough to undergo autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (ASCT) due to age or comorbidities. The definition is not strict and ASCT eligibility may vary from one center to another.

-

Elderly (older adults): Patients aged ≥65 years.

-

Very elderly: Patients aged ≥75 years.

-

Frail patients: Patients considered weaker and more vulnerable than their age-matched counterparts.

Presence of older adults in clinical trials

An important proportion of older adults that we see in clinical practice would not have been included in most clinical trials. Some of the reasons for exclusion from clinical trials are predefined upper limits for age or frailty and comorbidities, such as renal impairment, history of neuropathy, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of ≥3 or concomitant medications.7 For this reason, elderly subpopulation analysis of clinical trials represents a population that is fitter and less vulnerable than real-world patients.

This means that there is a lack of evidence-based data on how to treat frail MM patients. Most recommendations on how to treat this group of patients are based on expert opinions and clinical judgment. Therefore, there is an important need to correctly assess patients’ frailty and design clinical trials specifically for these patients.

Frailty assessment

Frailty assessment in MM varies from one center to another and can be divided into four main parts:

-

Frailty tools

-

Cognitive screening

-

Risk of falls

-

Nutritional status

The purpose of frailty assessment is to detect any potential impairments that could be optimized or addressed and be able to administer the best possible therapy.

Moreover, a recent study suggests that frailty is a dynamic parameter that improves or deteriorates in more than 90% of patients over time.8 Thus, frailty should probably be assessed not only at diagnosis but also periodically during treatment in order to optimally adjust therapy and dosing to what the patient can tolerate.

Frailty tools in MM

There is no specific tool to evaluate the eligibility for ASCT. Some centers use the hematopoietic stem cell transplant comorbidity index (HCT-CI),9 but this score was established in a cohort of patients who were destined for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), which is a very different population. Most centers apply an age cut-off between 65−70 years old to consider a patient transplant ineligible.

Several frailty tools have been developed and proposed to assess frailty in transplant-ineligible patients with MM. Table 1 summarizes the most frequently used tools.10 They all have age as a common parameter, and it is possible for patients to be labeled as frail for age alone.

The International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) frailty score is considered the gold standard and classifies patients into three categories: fit, intermediate fit and frail patients.11 This score predicts mortality and the risk of toxicity in first-line treatment. Recently, a modified version of this score is the Simplified IMWG frailty score12 was developed, which substitutes the more complex geriatric assessment by the ECOG and has the advantage that can be applied retrospectively to most trials (Table 2).

Cognitive function screening

Several cognitive function tools can be used as a part of the frailty assessment. For instance, the Mini-Cog test represents a simple and quick way of assessing cognitive function.13 No special training is required to perform the test, and it typically takes approximately three minutes to complete. It consists of three parts: the physician names three words, the patient draws a clock (two points if correct) and the patient repeats the three words (one point for each word). If a patient has a score of 2 or less, they will likely benefit from a referral for neuropsychological evaluation.

Risk of falling assessment

Turn-up and Go (TUG) is a simple test that can be quickly performed at the clinic and it only needs three objects: a clock, a chair and a 3-meter measurement (Figure 2).14 If the patient takes more than 13 seconds to stand up, walk three meters and sit down, they are at high risk of falling and a referral for physical therapy is highly recommended.15

Nutrition screening

Nutritional status should be assessed in all MM patients including the measurement of body mass index (BMI), screening for diabetes (glucose, HbA1c), vitamin B12 and albumin dosing. Referral to a nutritionist or endocrinologist is highly encouraged if the presence of malnutrition and/or diabetes is suspected.4

Limitations of frailty assessment

Frailty assessment is an efficient and cost-effective way to personalize therapy and reduce toxicities. However, it has several limitations. It is perceived as time-consuming and therefore not routinely used by many clinicians. In addition, age is present in all the frailty tools. There is an unmet need to develop age-agnostic tools that can discriminate patients with the same chronological age but different fitness status.17

The very frail and those with an ECOG of 3−4 are not taken into consideration by any of these tools, and these patients are considered the same as those with an ECOG of 2. Nevertheless, tailoring therapy is especially important in these very fragile patients.

Moreover, frailty tools should improve by incorporating biomarkers, such as markers of cellular senescence (DNA damage, telomere length and cell-cycle arrest), which are currently being explored.18

Treatment of elderly patients with MM

The MM treatment landscape has significantly improved in the last 20 years, with important survival gains being achieved, even in the older-patient population.19

Treatment of newly diagnosed elderly patients with MM

Several treatment combinations have been tested in phase III clinical trials designed for transplant-ineligible patients. These studies were not specifically designed for old and/or frail patients. Therefore, these results should be interpreted with caution.

These are the most important trials for transplant-ineligible patients (Figure 3):

-

The SWOG-S0777 trial: lenalidomide-bortezomib-dexamethasone (RVD) (compared to lenalidomide-dexamethasone [Rd]) is administered for six months followed by maintenance Rd until progression. Only 38% of patients were >65 years old.20

-

The MAIA trial: daratumumab-lenalidomide-dexamethasone (DRd) (compared to Rd) is administered until disease progression. Around 44% of patients were >75 years old and 46% of the patients were frail.21

-

The ALCYONE trial: daratumumab-bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone (D-VMP) (vs VMP) is administered during eight cycles, followed by a daratumumab maintenance until progression in the D-VMP arm (but no maintenance in the VMP arm). Around one-third of patients were >75 years old.22

In Europe, the most frequently used regimens for MM treatment are DRd (based on the MAIA study) and D-VMP (based on the ALCYONE study). The MAIA trial demonstrated an unprecedented progression-free survival (PFS) of 62 months, with a median overall survival (OS) not yet reached and anticipated to be approximately 85 months.21 The quadruplet D-VMP regimen (ALCYONE) demonstrated a median OS of 82.7 months (versus 53.6 months with VMP).23

All these trials, even MAIA which includes an important rate of frail patients, do not represent the real-life patient population. All of them excluded patients with creatinine clearance <30 mL/min and none of the patients with an ECOG of 3−4 were included.

Frailty subanalysis of clinical trials

Most clinical trials that include transplant-ineligible patients have reported subanalyses for frail and elderly subgroups, such as the one reported for the MAIA trial24 or the ALCYONE trial.25

Frailty subanalyses of these clinical trials concluded that the triplet combination is better than the doublet in the older/frailer population. Interestingly, treatment discontinuation rates are often equal or inferior in the triple arms compared to the doublets in these patients. Nevertheless, frail patients still present with inferior PFS/OS and a higher rate of toxicities than the rest of the cohort.

Nevertheless, these subgroup analyses were performed post hoc and should be interpreted with caution. Importantly, as mentioned above, these do not reflect real-life patient population.

Use of steroids in older patients

Corticosteroid medications have been used in the treatment of MM therapy for over 40 years. Its addition to other MM agents is thought to improve their efficacy and promote synergistic effects.26

However, steroids are poorly tolerated in the long term, even in younger patients, leading to significant toxicities such as infections, diabetes mellitus, osteopenia and psychiatric events.27 Moreover, its immunosuppressive effects could reduce immunotherapy efficacy and several studies reflect that patients prefer treatments with limited steroid use.28

A recent Italian phase III study investigated shortening dexamethasone exposure in intermediate-fit newly diagnosed MM patients. Patients were switched to reduced-dose lenalidomide maintenance without dexamethasone after nine Rd cycles. This approach showed similar outcomes, with a better safety profile compared to standard continuous Rd.29 Early discontinuation of dexamethasone after only two cycles of DRd is currently being evaluated in the French IFM 2017-03 trial, with promising preliminary results.30 In addition, the phase Ib PAVO trial shows that tapering corticosteroid premedication before subcutaneous daratumumab is a safe approach, without compromising efficacy in patients with relapsed/refractory MM.31

Most clinical trials in MM already recommend reducing by half the corticosteroid dosing for patients who are older than 70−75 years. In the next few years, corticosteroids are poised to be further reduced or even abrogated in the treatment of older patients with MM.

Suggested treatment algorithm for frail patients with newly diagnosed MM

As already stated, clinical trials propose a standardized induction treatment for the transplant-ineligible patient population with MM. However, it is vital to adapt treatment for those patients who are older than 65 years. In this sense, several approaches have been suggested to tailor first-line therapy according to the IMWG Frailty Score at diagnosis (Figure 4).

If eligibility for HSCT is uncertain at diagnosis, optimal induction should not differ from that in younger patients and could be adjusted for each cycle based on tolerance.

For intermediate-fit and frail patients, choosing a regimen with an abbreviated course of dexamethasone is probably the best strategy, with dose adaptation of each anti-myeloma agent, as suggested in Figure 3. If treatment is well tolerated, dosing may subsequently be escalated.

As previously discussed, triplets should be favored over doublets whenever possible, also in the older patient population.

For those very frail patients with an ECOG of 3−4, starting with a single agent or a doublet is possibly the best option to avoid early discontinuation and early mortality. Fitness may improve with disease control. For this reason, it is important to perform an ongoing dose adjustment and try to reach the optimally tolerated dose.

Treatment of relapsed/refractory elderly patients with MM

Currently, most transplant-ineligible MM patients are treated upfront with DRd until progression. For this reason, patients progressing after this approach will be refractory to both daratumumab and lenalidomide.

In this setting, choosing a proteasome inhibitor as the backbone for second-line therapy seems to be the best option, with either bortezomib (pomalidomide-bortezomib-dexamethasone [PVd], bortezomib-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone [VCd]), carfilzomib (carfilzomib-pomalidomide-dexamethasone [KPd], carfilzomib-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone [KCd]) or ixazomib (ixazomib-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone [IxaCd]). Regarding carfilzomib, there is little data regarding its use in frail patients, and it should be used with caution and preferably avoided in patients with preexisting cardiopathies or uncontrolled hypertension. Other potential alternatives in this setting are pomalidomide-based regimens such as PCd (pomalidomide-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone), EloPd (elotuzumab-pomalidomide-dexamethasone) or Pd (pomalidomide-dexamethasone).

New immunotherapies

New immunotherapies, such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy and bispecific antibodies, have become an essential part of the treatment of relapsed/refractory MM. They present with some unique toxicities, such as cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurotoxicity and an important risk of infections. There are very limited data on the use of new immunotherapies in the elderly patient population. Elderly subgroup analysis in some of these studies shows comparable or even superior efficacy to that observed in younger patients. Nevertheless, the elderly patients in these trials are highly selected and do not represent real-world elderly patients. Table 3 shows the patient characteristics of the phase II KarMMa study evaluating the anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy idecabtagene vicleucel and the phase II MagnetisMM-3 study evaluating the anti-BCMA bispecific antibody elranatamab.

A complete frailty assessment (such as that mentioned at diagnosis, including a geriatric assessment, neuropsychological and nutritional evaluation and prompt physical therapy) should be performed before each line of therapy. This is especially important in the setting of new immunotherapies to optimize the patient before starting these treatments.19

Treatment perspectives for older patients

There is an important need for clinical trials focusing on elderly and frail patients, who are commonly excluded from clinical trials due to comorbidities. The ongoing phase III UKMRA Myeloma XIV FiTNEss trial (NCT03720041) explores the idea of performing a frailty-adjusted induction treatment versus standard up-front dosing followed by toxicity-dependent reactive-dose modifications during therapy.36

Bispecific antibodies, such as teclistamab in the IFM 2021-01 trial (NCT05572229), are currently being explored in the first line in elderly patients and will likely play an important role in this setting. In addition, belantamab mafadotin, an anti-BCMA antibody-drug conjugate, is administered in an outpatient setting at relatively long intervals of three weeks and may be potentially suitable for frail patients in combination with other agents.37 However, it presents significant ocular toxicity, and the drug is not yet approved in Europe.

New-generation immunomodulatory drugs, the so-called CELMoDs (Cereblon E3 ligase modulators), such as iberdomide38 and mezigdomide39 are oral and well-tolerated agents and therefore will possibly have a key role in early treatment lines of elderly patients.

Moreover, more diligent and standardized quality-of-life analyses are needed, especially in the frail patient population setting.

Conclusions

Frailty assessment of MM patients older than 65 years should be integrated into common clinical practice and harmonized across studies. Most elderly patients will only receive one line of therapy. Therefore, the best treatment options, whatever they are, should be used in the frontline. However, treatment dosing should be adjusted to frailty, with ongoing adaptation and try to reach an optimally tolerated dose. Trials focusing on frail and very frail patients are needed.

Conflict of interest

Yan Beauverd has received honoraria for advisory board meetings from AbbVie, BMS, Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Novartis. These funding entities did not play a role in the development of the manuscript and did not influence its content in any way. Other authors have declared that the manuscript was written in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Author contributions

The authors have created and approved the final manuscript.

_frailty_score__334375__an.jpg)

.jpg)

_frailty_score__334375__an.jpg)

.jpg)